Claire Harris was rolling them bones. Like any hot shooter, she wasn't stopping now.

Here they came: Naturals. Snake Eyes. Yo-levens. Everything hard. And everything easy.

She was on a mission.

See, Claire Harris — now Claire Bhogal — is not a gambling addict. She's an information addict.

And, like we said, nobody would dare try to stop her. Not that anybody there at the time would have even considered it. They were all for it. A family tradition, even.

We'll explain.

A Probability She's Going to Love This

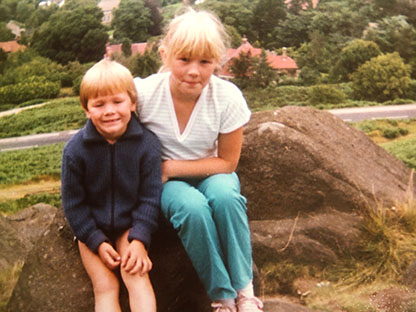

Claire Bhogal was born in Leeds in the northern England, daughter of Joyce and Bernard, older sister to brother Paul. Now married to John and mother to Amy, 8, and Arthur, 5.

Claire comes from a family that prefers to know, to understand, to have the information at hand. Her dad? Engineer. Little brother Paul? He's all grown up and a physics teacher now. Her grandmother on her mother's side? School teacher. A couple of uncles were mathematicians, like Claire. She likes math. A lot.

"There’s a logic there. There's a process you can follow. There's nothing more beautiful than a nice proof," Claire said with a laugh. "I think it is very satisfying. There's a certainty.

"But there's an ambiguity as well. As I went on to my statistics career, you start to learn more about variation — measurement variation and other things — you start to get maybe a different perspective."

That dice story? It spoke to everything Claire likes about her work: Her early interest in math and logic, that pleasing feeling of really knowing and then the uncertainty that can come when math meets chance in an experiment in her maternal grandmother's house, which her family visited every Sunday (dad's side on Saturdays).

Here's how she tells it: "I remember, we were doing probability experiments. We did a lot of throwing dice and recording what results we got for each dice, actually doing bar charts to work out which number was most frequent. We waited until we got 100 of a particular number.

"We had parameters for the experiment. We knew what we were trying to do. It was pretty well defined. I guess we must have rolled the dice, I don't know, 500 times or something."

Rolling was just the start. Then the fun started.

"We had this massive piece of paper — I don’t how big it was, 8 foot long or something — literally marking on every single number that we rolled on the dice. That's the bit that I really enjoyed. And interpreting the data. That really resonates with the role I’ve gone on to do."

Just like any 6-year-old would do. Sure.

For the record, the 3 side of Claire's dice reached 100 first.

"We spent a lot of time at our grandparents playing games, playing board games, card games and things like that," said her brother Paul. "Grandma Whiteley was a primary school teacher. Our grandma Whiteley taught me to read. She saw Claire was interested, gave her the tools and stood back and let her do it."

The Next Set of Reproducible Results

That encouragement helped lead where Claire is today, with stops at Durham University for a bachelor's in math and the University of Sheffield for a master's in statistics, where she worked on a project with a local hospital to sort out which test was best determining whether people had anemia. The benefits were clear: less blood required from patients, less cost to hospitals to run fewer tests, more time to begin treatment.

"That’s really inspiring, that you can take those numbers and turn them into something meaningful that has an impact on people’s lives," Claire said.

She and her family are now in Witney, where she’s Abbott's Research and Development Director managing the UK R&D team in Diabetes Care. Her résumé includes Navigator and now FreeStyle Libre, including living in Alameda, Calif., for a time focusing on the device's factory calibration.

Does she remember a time when she thought the FreeStyle Libre system could take the step to become the life-changing technology it is for so many?

"If only it was just one moment," she said, again with a laugh. She does that.

"I was involved in the technical performance, designing the sensor so that every single one is manufactured in the same way. Manufacturing steps had to be designed and optimized. And we've got control systems that make sure we're measuring and checking the sensor at multiple stages.

"So that was really the focus that we had, to make sure that we could create a sensor that was robust and could be manufactured in a reproducible fashion."

Designing a process to create reproducible results? Not all the different from rolling dice hundreds of times to find the answer.

'An Area Where Females Can Flourish'

From the strong example Claire's grandmother set to living her own life, Claire has seen the positive power when women working in STEM (science, technology, engineering and math) can set the stage for girls growing up with similar dreams.

Fact is, she never doubted herself pursuing a career in mathematics.

And her advice is simple: "Follow what you really enjoy doing. And just be curious."

Her brother Paul saw that first hand.

"Claire was an avid reader," he said. "She was also very interested in music. There's always a link, isn't it, between music and mathematics? She was a cello player. Later on, she was a clarinet player. She was also interested in languages, French and Spanish. And again, there's a link between mathematics and languages, isn't there, in terms of patterns?"

And sport. Among varied interests, Claire was a "keen swimmer," Paul said. Her choice among football ("soccer," for you Americans) clubs was a bit curious, as well. Her family hails from Leeds but she's a Sheffield United fan.

"We forgive her, we forgive her," Paul said, laughing, a family trait. "Nobody’s perfect."

Among STEM students, Claire said she's seen more of a gender balance among those pursuing math, though the progress may have slowed in the last generation.

"I was talking to a colleague about this the other day and in some ways, I don’t think that's moved on. I went and looked at the statistics," as you’d expect, "and I think it's stayed very static over the last 20 years — the proportion of females going into mathematics — which is interesting.

"I think there have been a lot of focus on maybe some of the other areas to encourage more females to enter. Maybe the 'M' gets forgotten a little bit in 'STEM.' I certainly didn't feel out of place when I was studying. And certainly, going in to statistics, again that was pretty evenly balanced as well."

That experience has continued in her work life.

"Our statistics group here (at Abbott) is again pretty much 50-50 in terms of males and females. So it does seem to be an area where females can flourish. And I think part of that actually is going into a statistics career, a lot of that is about helping people and translating problems."

For Claire Bhogal, whatever the potential vagaries, a life helping people through math all added up. It was never much of a roll of the dice after all.

Please be aware that the website you have requested is intended for the residents of a particular country or region, as noted on that site. As a result, the site may contain information on pharmaceuticals, medical devices and other products or uses of those products that are not approved in other countries or regions.

The website you have requested also may not be optimized for your specific screen size.

FOLLOW ABBOTT